Chasm, 2002

The commanding settings for Linda Cummings’s Slippages include steel plants, sports stadiums and cathedrals, along with equally iconic landscapes, vast and majestic. Floating above them are delicate garments, wispy as tattered clouds: lingerie, aloft. A series of luminous black and white photographs made over a ten-year period beginning in 1992, the Slippages show women’s slips tossed into the air by the artist and caught there by the camera. Each, the artist explains, was carefully chosen, from thrift stores, for the weight and color of its fabric, and for the traces they bore of bodies they once graced—tangible indexes, like photographs, of absent lives, now animated by wind. Amid rising globalization in an increasingly digitized world, the Slippages pit an old, rock-ribbed industrial America against its long-invisible agonist: a proudly feminine spirit discovered to be blithely triumphant. These risky improvisational gestures were staged using 35mm film—Cummings judged successful only one or two shots from every 36-exposure roll—and hand-printed by the artist, without post-production manipulation, on silver gelatin paper. The images are by turns tender, comic, heroic and devastating.

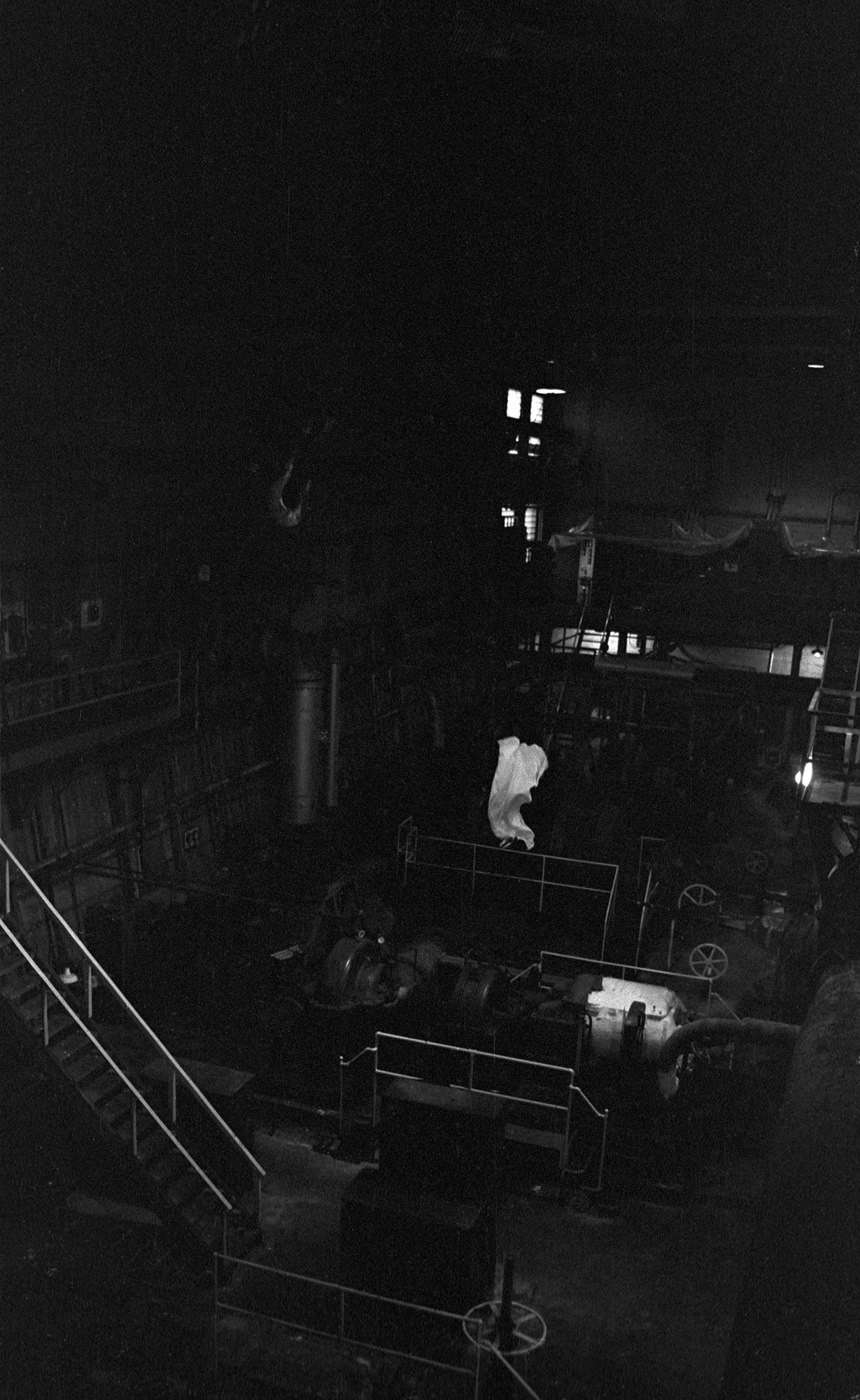

The first of the ten portfolios comprising Slippages is “Fissures” (1992-2002), which features natural wonders: Arizona’s Grand Canyon; Chaco Canyon, in New Mexico; a geyser and a waterfall in Iceland Against these landscapes, the undergarments, leaping and soaring, seem especially fearless. The “Fissures”’ invocation of sublimity shifts to the explicitly spiritual with the photographs in “Ecclesiastic” (1994), some taken in the colossal St. John the Divine, in New York, where one slip glides over an altar and another sails over a baptismal font. In New Orleans, Cummings set the undergarments afloat in the famed St. Louis aboveground cemetery, where they hover in a way that seems hesitant and particularly ghostlike; Cummings calls them ambiguous, for the way they slide between living and dead, public and private. By contrast, “Steel City” (1996) finds the slips spry and stealthy, intruding with mischievous ease on the grim precincts, historically masculine, of an abandoned steel-making plant. Trouble-making “shape shifters,” in Cumming’s description, they dance amid the steelworks in Belly of the Beast, gleam in the nighttime Black Cloud, sail grandly over the thicket of black exhaust pipes in Exchange Values.

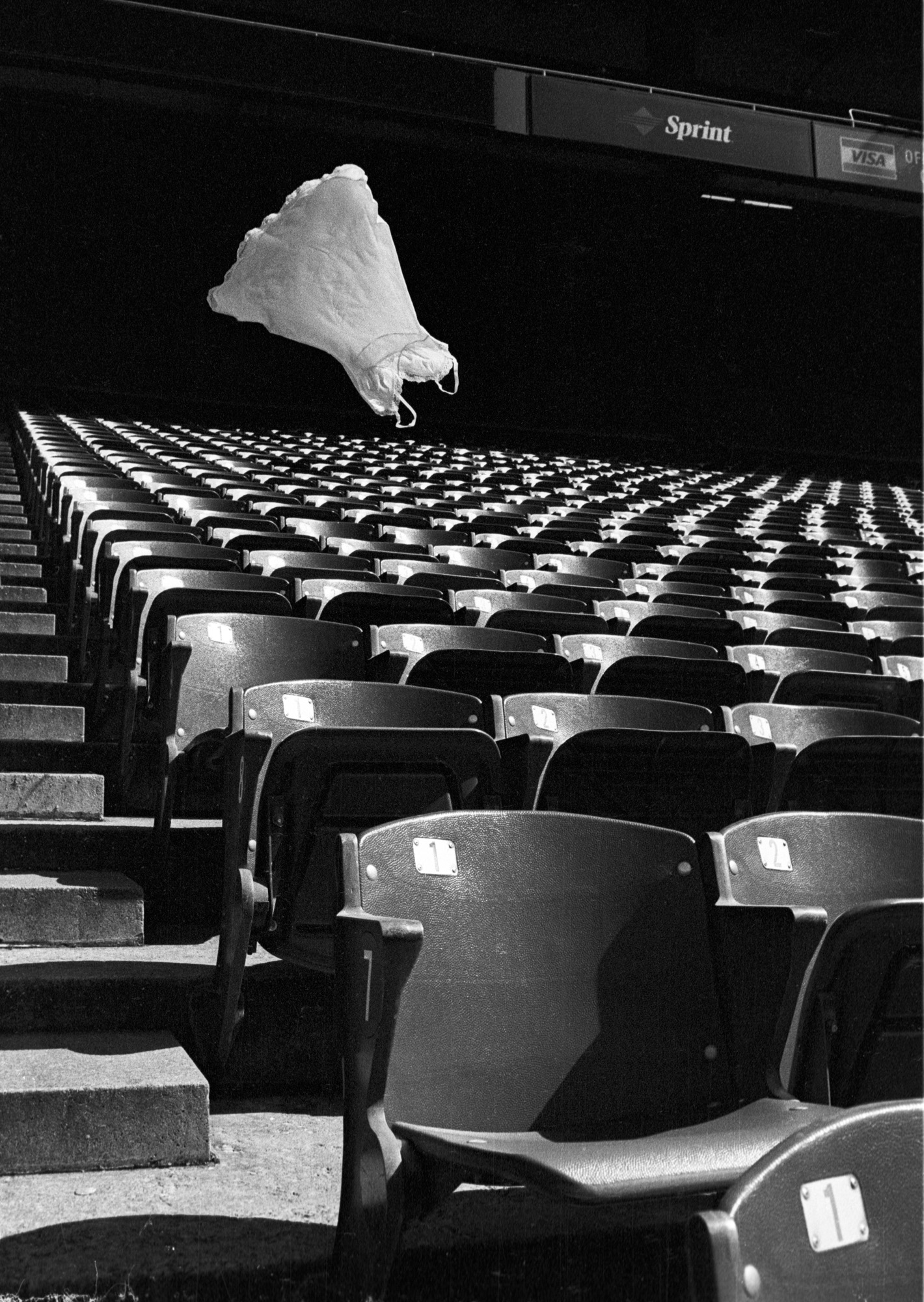

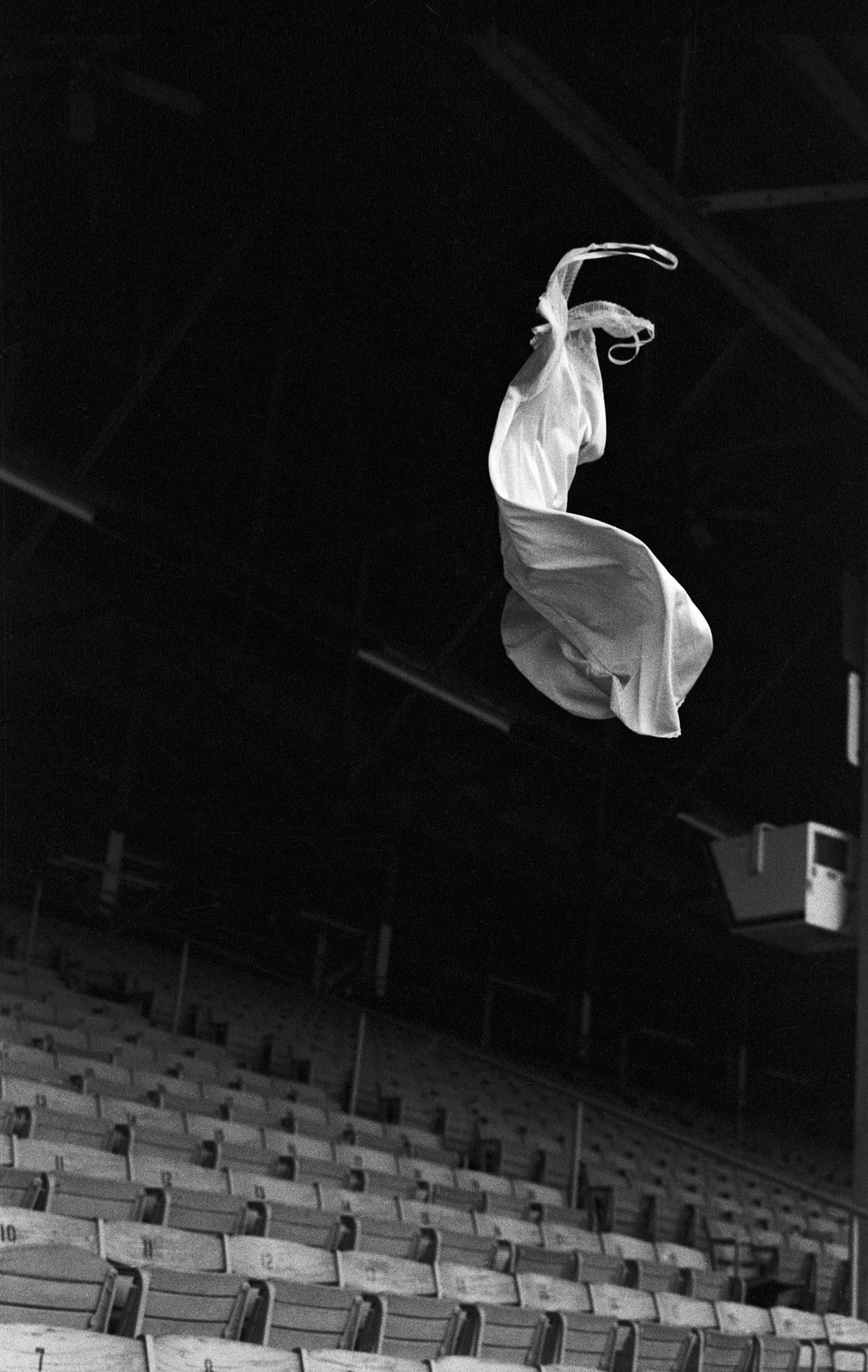

With “Ovulator” (1997), the lacy undergarments find themselves in sports stadiums, structures again strongly identified as male, and modeled on Classical landmarks—the playing fields of Olympic games; the Roman Coliseum, scene of gladiatorial combat. Entering into the spirit of competition, the slips become athletic and even muscular; one hurls itself across a gridded field like a quarterback going for a touchdown. But most threatening among the portfolios is the one set in Three Mile Island (1998), a nuclear power plant that suffered a partial meltdown in 1979. A single reactor tower looms ominously in each photo. Seen against turbulent skies, the slips appear uncharacteristically heavy, as if made of damask, their billowing forms rhyming with the dark clouds above.

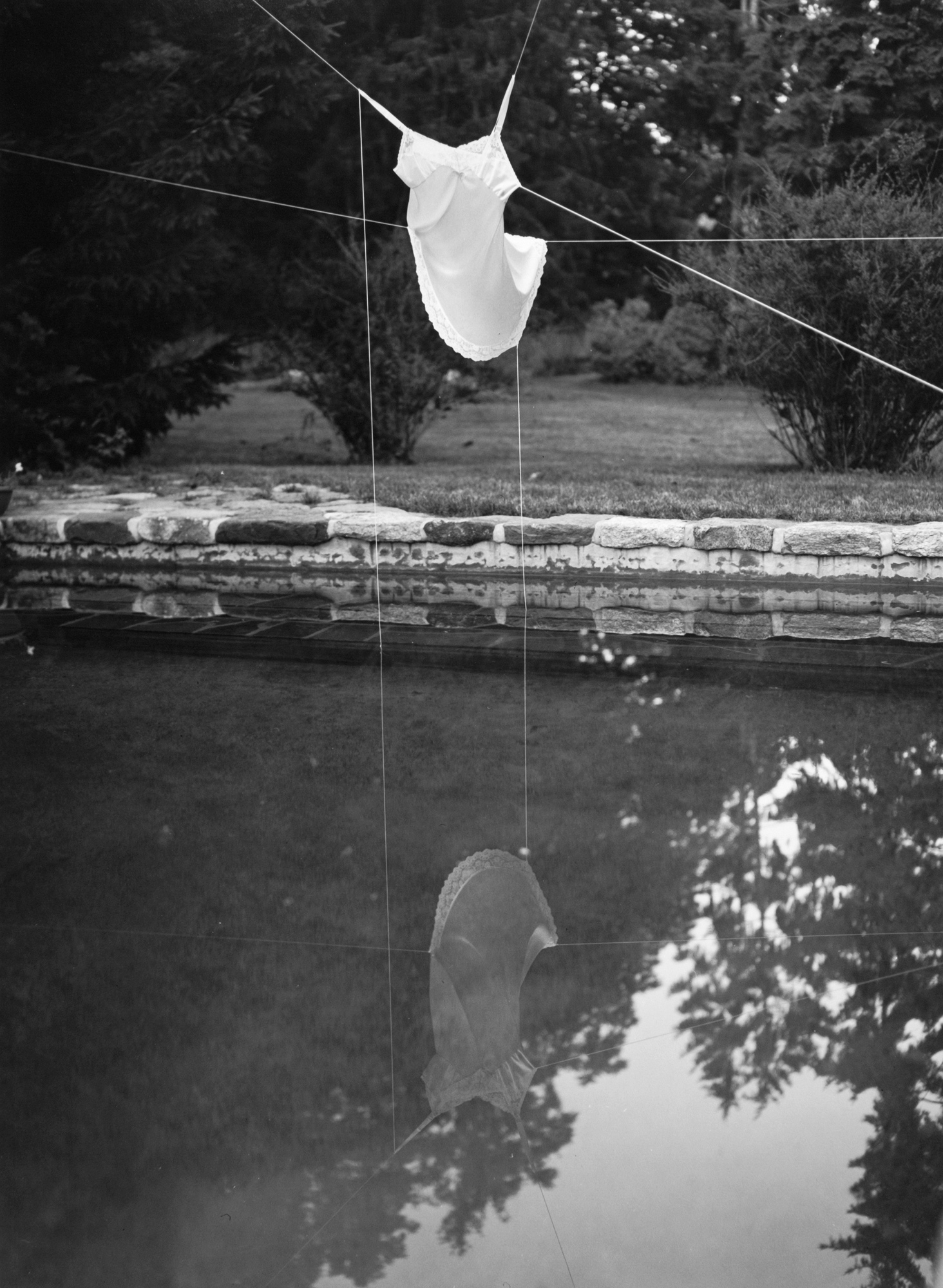

In the early photographs the slips and structures framing them are fairly cleanly opposed, but the relationship between them grows steadily more complicated. “Anatomy of a Fantasy” (1998) finds silky undergarments strung along guy wires stretched over a pond shaded by greenery. The choreography is graceful but also constrained, if delicately, and the tone is a little melancholy. Cummings explains that this series was taken while she was artist in residence, under the auspices of the New Jersey Printmaking Council, at the Martha Brooks Hutchinson estate, which at the turn of the 20th century hosted athletic events for women. The guy wires, she says, invoke the “strings attached” constraints that barred women from competitive sports. Similarly, nostalgia shadows a photo from the Saratoga Racetrack portfolio (2000), set in an old theater, although the slips here deliver a lively and dramatically lit performance, jumping and tumbling over weathered wooden chairs. This image is from the portfolio “Stages” (1992-2002), which includes a photograph of the Statue of Liberty diminished by distance, its valiantly raised arm seeming to have just released the slip that flies through the air like a grand—and dramatically abandoned—banner of freedom (Liberty, 1995). In Screen Memories (2001), a drive-in theater’s huge blank screen provides the backdrop for a bit of lingerie pantomiming a glamorous movie star. Nude Descending the Staircase I is named for a famous painting by Marcel Duchamp, and also acknowledges Duchamp’s 3 Standard Stoppages, based on three lengths of string dropped onto waiting canvases; in Cumming’s composition, a rather grim stairway fails to dampen the spirit of the nearly transparent slip that wafts above its steps.

With “Wetlands,” (2000-01), the photographs, ethereal and luminous, grow almost abstract, both the slips and the landscapes they inhabit blurred by apparent motion—which, as Cumming observes, is a naturally occurring abstracting device, “intended to shift visual and psychological parameters back and forth between perception and recognition.” Similarly, she explains, the use of infrared film “invites both recognition and misrecognition.” The series concludes, in Cummings description, “with a merging of subject and object into one dream-like impression.” By contrast the final portfolio, “Operating Theater” (2002), is icily crisp. In an old-fashioned surgery (it is part of the old St. Vincent’s hospital in New York City, to which Cummings gained access with support from the Susan G. Komen Foundation), a pair of inquisitorial lights looms over an operating table; here, the slips assume the identity of souls rising from absent bodies. But these ominous images are also tinged by a sly humor that can be felt throughout the series. From the beginning, emblems of authority—whether denoting medicine or religion, industry, culture or entertainment—try in vain to pin down and sedate figures that utterly defy them, buoyant sprites that are jubilant and irrepressibly free.

Cummings’s career in photography has taken an unusual path. Following her education at Cleveland Institute of Art and the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, she was employed for eight years as a photographer by Mack Trucks, Inc.. In her independent work, she was working in black and white, inspired by both experimental and documentary photography of the early twentieth century: Man Ray, Rodchenko, the Russia Constructivists. While she was interested in the formal and conceptual issues they explored, she was also drawn to politically driven photography of the 1930s and ‘40s by such trailblazers as Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange; Cummings has said that like them, she was driven by the conviction that “photography could be used as a way to change the way people see things socially, not just perceptually.” Indeed, her Cross over Bethlehem (1996) is taken from the same vantage point as Evans’s iconic A Graveyard and Steel Mill in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, of 1935. Referring to politics of the Slippages more generally, Cumming recalls, “I was thinking of how the myopic point of view of the single lens reflex camera actually reinforces the one-point perspective that characterizes most forms of totalitarian thought.” She was also thinking of such pioneering feminist artists as Mary Kelly who boldly took on the even more pervasive constraints imposed by patriarchy. Perhaps not surprisingly, challenging institutional power often involved a certain amount of subversion. Several of the sites Cummings used, including the steelworks and the stadiums, presented considerable challenges of access, and security staff are sometimes just out of the frame in these images, “making wisecracks about women and balls and slips” and snorting their contempt. Cummings learned to take extra film to her shoots, handing off a blank roll when an exposed one was demanded.

There were, needless to say, other obstacles too. Gauzy, silky garments tossed into the wind are hard to control; while Cummings by necessity embraced chance, she soon began stiffening hems and seams with copper thread (invisible in the photographs) so the slips would have more body. But a fundamental condition of working with analog equipment remained: the lag between exposing the film and developing it means one doesn’t know, for a time, what has been captured. The surprises of the darkroom create a kind of magic that is captured metaphorically in the fugitive, ghostlike presence of these slips.

That sense of the magical, even supernatural, in the Slippages raises an inescapable comparison with spirit photographs of the late 19th century. It has been observed by many writers that spirit photography, and the Spiritualist movement of which it was a part, were inseparable from the explosion of new technology associated with the rise of the industrial age: electricity, telegraphy, telephones, X-rays, radiation and radio waves were inventions and discoveries that harnessed invisible and impalpable sources of power, permitted transmission of sound and imagery across distances, and allowed for the hidden to be shown. Indeed from the start, all photography was seen as allied with the supernatural. The famous French photographer Nadar, ticking off the century’s technological achievements, asked rhetorically, “But do not all these miracles pale . . . when compared to the most astonishing and disturbing one of all, that one which seems to endow man himself with the divine power of creation: the power to give physical form to the insubstantial image that vanishes as soon as it perceived, leaving no shadow in the mirror, no ripple on the surface of the water?”

In the United States, the rise of these seemingly miraculous technologies coincided with the Civil War, its avalanche of death creating an aching thirst for contact with the departed. Spiritualism answered that need with techniques ranging from séances at which the dead spoke through mediums, to photographs portraying their shadowy presence. Tom Gunning notes an analogy between the darkness needed to protect the sensitized photographic plate from exposure and the darkness in which séances were held. Such was the desire for connecting with the deceased that even when the photographers admitted deceit, some clients insisted the images bore true witness.

Marina Warner offers an explanation for this credulity, arguing that spirits, astral bodies and subtle matter had grown so conventionalized as to seem natural. Hiding in plain sight, these conventions can nonetheless be described: “It is the quality of lightness above all that distinguishes the spirit element—lightness in both its luminous and its weightless aspects. . . . Spirits and souls take wing; they are made of light and of lightness; the gravity of the world and of flesh does not hold them in its grasp,” Warner writes, noting that the Greek word ‘psyche,’ a word for ‘soul,’ was also used for ‘butterfly’ or ’moth,’ and that the Egyptian ba, which also means soul, resembles a bird. A connection is made to the Christian Holy Ghost. Surely one exists as well to Cummings’s levitating, semitransparent slips. A resurgence of interest at the turn of the millennium brought a major exhibition of spirit photography to the Metropolitan Museum in 2005. Among the artists included in related exhibitions were Zoe Beloff, Ann Hamilton, Susan Hiller, Bill Jacobson and Francesca Woodman. By then, the Slippages had concluded, having anticipated an era of eager attention to the astral and the spectral.

However powerfully they suggest bodies gone ephemeral and illusory, the Slippages belong securely to the analog world. Indexical in the old fashioned sense of mechanical reproduction, they are written indelibly by light on photosensitive film, and then again printed by light, just as they are, on photosensitive paper. To be sure, they are staged; there are things happening off camera we don’t see, including the copper wires and the snickering guards, and most of all the photographer herself, setting each slip in motion and jumping away. But they are factual and physical in a way that is now an object of nostalgia. So are the enduring icons of institutional power that Cummings has documented, however rusted and scarred. In considering their taxonomy, Cummings takes a place beside photographers who document industrial and military might as different as Bernd and Hilla Becher, Mitch Epstein and Trevor Paglen.

Like them, Cummings seldom represents people. More characteristic of her recent work are photographs of nature—for instance, of bodies of water whose surface coincides with that of the photographic print. As with Slippages, these images capture a fragile beauty, found in environments vulnerable not only to the ravages of the anthropocene but also to photoshopped fantasies—and to other depredations of the digital age, which has a much bigger physical and carbon footprint than terms like cloud computing suggest. But the two features that are perhaps most salient to photography in the era of digital media are its imbrication in the social and its susceptibility to falsehoods. It is a commonplace that digital media have made fabrication photography’s default position, further undermining the medium’s credibility, while conforming to a culture-wide departure from commitment to truth. And many observers warn that face-to-face contact is giving way to smart devices and social networks, additionally vitiating physical experience.

Indeed some believe that the balance between human and artificial intelligence has already tipped—that vision itself has become a function of our smartphones, always at the ready, telling us what to look at and adjusting the record of what we see. The lenses on such devices are “basically rubbish,” writes media artist and theorist Hito Steyerl, but the quality of the images they produce is excellent because the embedded technology “scans all other pictures stored on the phone or on your social media networks and sifts through your contacts. . . . the algorithm guesses what you might have wanted to photograph now,” making it “not in content but form . . . truly social.” That is, Steyerl contends, “As humans feed affect, thought, and sociality into algorithms, algorithms feed back into what used to be called subjectivity.” Nathan Jurgenson insists otherwise. “The Web,” he says, “has everything to do with reality; it contains real people with real bodies, histories, and politics.” Jurgenson urges us to recognize that “the digital and physical are enmeshed,” and that what we do while connected is inseparable from what we do when disconnected. If contention is rife among the theorists of the digital, most agree on photography’s new ephemerality. Where once it cheated death, nothing now lives a shorter life than a photo.

Born in the twentieth century, partaking of the nineteenth while engaging issues particular to the twenty-first, Cummings’s Slippages are perhaps most revelatory for the light they throw on gender politics. As she ruefully notes, “power is invisible to those who have it, and clear as day to those who don’t.” In part, she says, her mission was to create an apparition that lent presence to the unseen—and also to provide a luminous screen on which fantasies could projected. In fact, slips have a surprisingly robust associative life. A mere slip of a thing is a slender young woman, appealing, to some, precisely because she is unassertive. Unmistakably feminine, yet meant to help hide the female body, slips were consigned to obsolescence by the feminism of the late 1960s; in their afterlife, they serve, Cummings says, as figures of gender fluidity. Slips are also falls, as on ice; since Freud they have been, as slips of the tongue, revelations of thoughts otherwise unvoiced, revealing things the speaker often believes to be shameful—verbal underwear, exposed. Cummings instead gives us the slip as superhero—as Wonderwoman, leaping tall buildings in a single bound, flaunting what was once concealed. It is a bountiful gift.

NOTES

- Quoted in Alison Ferris, “The Disembodied Spirit,” in Ferris, Tom Gunning and Pamela Thurschwell, The Disembodied Spirit (Brunswick, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, 2003), 34

- Notably, William Mumler, spirit photographer’s first acclaimed practitioner, produced a photo of the newly widowed Mary Todd Lincoln with the shade of her husband.

- Gunning, “Haunting Images: Ghosts, Photography and the Modern Body,” in The Disembodied Spirit, 10

- Gunning writes that while the photos are often naïve, “they are evidence of a sort, images speaking (perhaps more poignantly due to their failure to convince) of the desire to believe, the desire for evidence of immortality and contact with the dead.” “Haunting Images,” 14

- Marina Warner, “Insubstantial Pageants: Spirit Visions, Soul Traces,” in Mark Alice Durant and Jane D. Marsching, The Blur of the Otherworldly: Contemporary Art, Technology and the Paranormal, Issues in Cultural Theory 9 (Baltimore, Center for Art and Visual Culture at the University of Maryland, 2006), 98-100

- Clement Cheroux, Andreas Fischer et al., The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult, September-December 2005

- “Blur of the Otherworldy” at the University of Maryland, 2006; “Disembodied Spirit” at Bowdoin College, 2003

- An exception is Cummings’s Times Square series

- Hito Steyerl, Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War (London and New York, Verso, 2017), 31-32

- Steyerl, 38

- Nathan Jurgenson, The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media (London and New York, Verso, 2019), 68

- Quotes of the artist are from a conversation in her New York studio on November 4, 2019, and from written comments emailed on April 17, 2020.

Nancy Princenthal is a New York-based writer whose book Agnes Martin: Her Life and Art (Thames & Hudson, 2015) received the 2016 PEN/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award for Biography. She is also the author of Hannah Wilke (Prestel, 2010), and her essays have appeared in monographs on Doris Salcedo, Shirin Neshat, Robert Mangold, Janet Biggs and Alfredo Jaar, among many others. Nancy Princenthal is a Contributing Editor (and former Senior Editor) of Art in America, she has also written for the New York Times, Artforum, Parkett, The Village Voice and elsewhere. Princenthal has taught at Bard College, Princeton University, and Yale University, and is currently on the faculty of the School of Visual Arts. Her most recent book Unspeakable Acts: Women, Art, and Sexual Violence in the 1970s, was published by Thames & Hudson in October 2019.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/24/books/review-unspeakable-acts-nancy-princenthal.html

Linda Cummings was born in Valley Forge, PA and studied fine arts at the Cleveland Institute of Art, Nova Scotia College of Art & Design and Rutgers University. Cummings lives and works in New York City and Branford, Connecticut. Since 1996 she has taught at the International Center of Photography in New York City.

Selected Images

Related Materials

Revisiting Slippages

Centennial Anniversary of 19th Amendment

Slippages

1992-2002

More Information

To learn more about this and other projects, or to request proposals for public or private commissions, please contact Linda Cummings Studio.